The Mid-12th Century was Wild

Full disclosure: The following set of ramblings is part of a longer form piece that I hopefully will complete in audio form. I will then post the script and all of its research and sources here, but until then, you’ll just get this tiny snippet of random thoughts.

What are you on about?

When we think about the 13th century, we probably think of the “High Middle Ages.” Popular conception often talks about knights, lords, and abstracted feudal politics that gets further abstracted when one considers the very definition of “feudalism.” This, my friends, is a conversation that has gone on for decades (and some might even say that the debate has waged since the Medieval Era itself), and as I am not a scholar of medieval history, I aim to not add my own unqualified voice into that discussion.

However, while I was combing through research for an upcoming piece, I discovered a rather strange set of random events that really made me think. From the 1240s-1260s, the politics of the Ayyubids, the Mamluks, the Mongols, the Kievan Rus, the Byzantine Empire, and many other polities somehow converged and shaped one another. In broad strokes, we saw the ascendency of the Mongol Empire, as it wreaked havoc across the Middle East, Eastern Europe, and the Caucasus Mountains. We witnessed the rebirth of the Byzantine Empire after over fifty years of fractured politics. There were the Crusades, the Reconquista, and the infamous fall of Baghdad.

In such a short span of time, the regional orders of Eurasia had collapsed and were radically altered. Over 500 years of Islamic rule in Spain had been reversed. Likewise, 500 years of Abbasid influence fell into a literal river of smoke and ash. 400 years of Kievan Rus suzerainty vanished. Sure, history clearly tells us that things were never stagnant nor stable. Muslim rule of Spain, or al-Andalus, had altered radically between the Caliphate, the Taifas, the Almoravids and Almohads. The same could be said of the Abbasids, who by the end were merely puppets to various Turkic states, like the Seljuks. However, there’s something vastly consequential about the mid-12th century that shouldn’t be overlooked.

Let’s take a look at a few examples.

To really illustrate just how cool and how important the mid-12th century was, I’m going to highlight three key dates that all span about a decade.

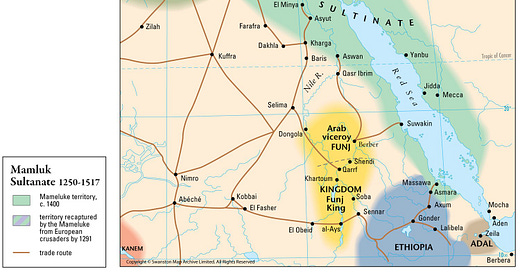

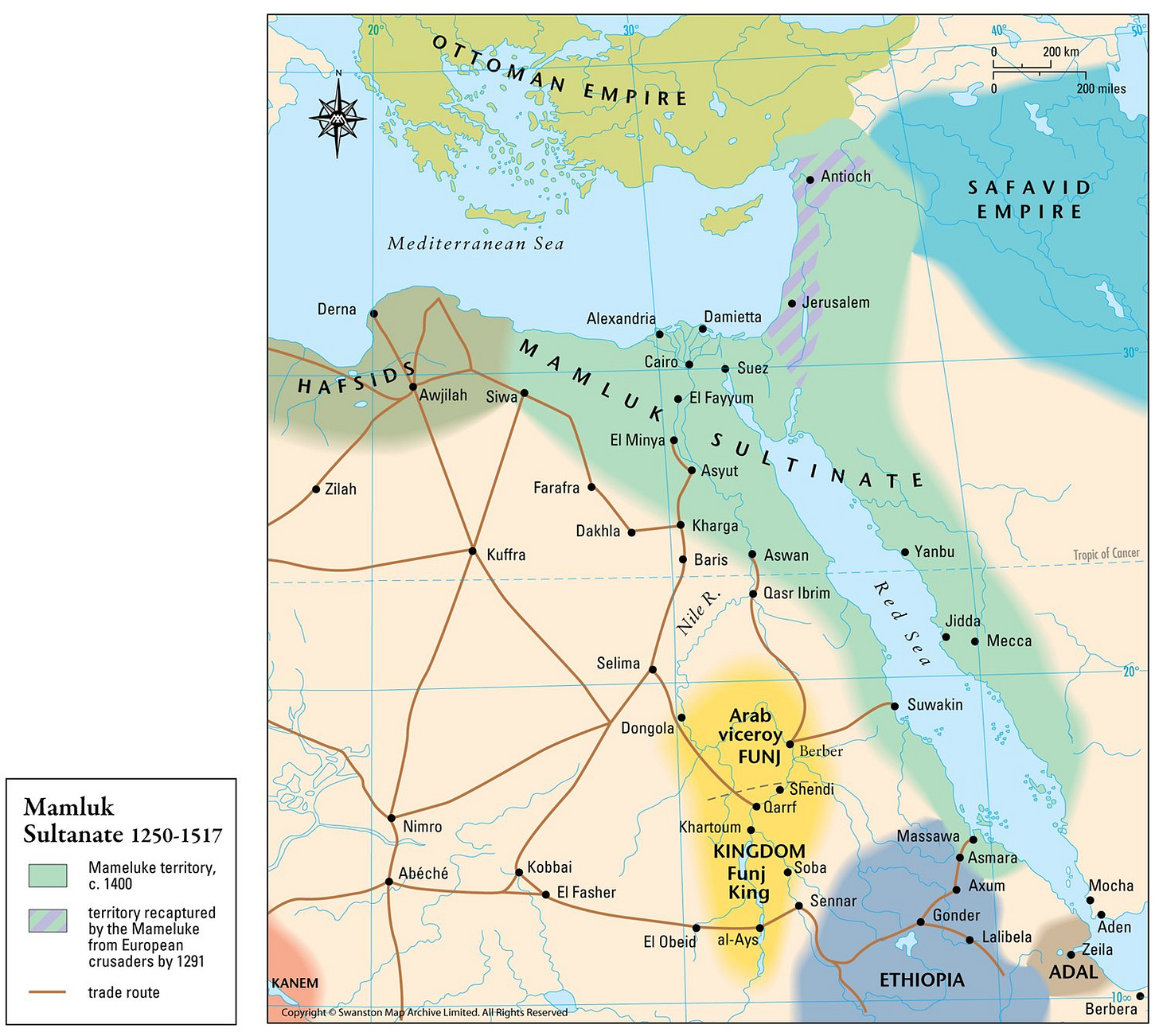

First: May 2, 1250 - The Mamluks

Ever heard of Saladin (more correctly transliterated as Salah ad-Din)? I bet you have. Kingdom of Heaven (I haven’t watched) talks about him and romanticizes the already romanticized history of Salah ad-Din and King Richard the Lionheart. Well, fast forward about sixty years and Salah ad-Din’s Ayyubid dynasty, which ruled Egypt, pretty much disappears. The Sultan Turranshah was attempting to make changes to his military, which at the time was ruled by a group of slave soldiers known as the Mamluk. Many of these Mamluks came from the lands of modern Russia, in an area known as the Cuman-Kipchak steppe. In the wake of the Mongol invasions in the 1220s and 1240s, a bunch of Cumans and Kipchaks (as well as Circassians and other groups) were sold as slaves by Venetians and Genoans and carted off to Egypt.

These slaves became the Mamluk and were pretty well versed in steppe tactics, and this elite force would influence George R. R. Martin’s concept of the Unsullied. Well, the Ayyubid Sultan Turranshah wanted to change this elite fighting force and put a new group of slave soldiers in charge. The old group, known as the Bahriyya, were having none of it. The Bahriyya had fought the Crusaders for decades including the crazy Seventh Crusade, which had the Medieval equivalent of D-Day. To be thrown aside after so much sacrifice almost certainly angered the Bahriyya. So, one day in 1250, when Turranshah was having a feast, the Bahriyya Mamluks assassinated the Sultan at his dining table.

Most historians would claim this date, May 2, 1250, as the start of the Mamluk Sultanate. The Mamluks would play a huge role in the next few decades and throughout the next few centuries. They would rival the Ottoman Empire, they would have an incredibly dynamic relationship with Renaissance Italy, and they would be the death dealers of the Latin Crusaders.

Source: The Map Archive

Second: 1256 - The Ilkhanate

The story of the Mongols is pretty much so well known and so well studied and so well documented in movies, podcasts, and horribly inaccurate Youtube videos that I don’t feel the need to go into many details about it’s early history. Instead, we’re going to skip forward to the ascension of Möngke Khan to the Mongol Empire in 1251. After a lot of subterfuge and politicking, the line of Ogedai would no longer hold the Mongol throne as Güyük Khan died of possible poisoning in 1248.

With Möngke and the House of Jochid in charge, the Mongol Empire set itself on a vast array of conquests. The brothers of Möngke would be thrown in all directions. The infamous Kublai was sent eastward to fight the Song Dynasty of China in a conflict that had lasted decades by this point. Hulagu, meanwhile, headed westward. In 1256, Hulagu arrived in Iran, and many historians cite this year as the start of the Ilkhanate.

The term “Ilkhanate” literally means “lesser khanate.” It was a subordinate political entity that pledged total allegiance to the Great Khan in Mongolia, in this case being Möngke. While the Ilkhanate would eventually emerge as its own independent entity, it was, at this time, still loyal to the Great Khan. As such, Hulagu would go on a rampage under Möngke’s orders. Sometime in early-1256, the Assassins of Alamut (yes, the Assassins from Assassin’s Creed, though these were the Persian branch) were completely destroyed by Hulagu. Then in 1258, Hulagu torched the great city of Baghdad, ending the Abbasid Caliphate.

In the wake of this, Mongol momentum reached a zenith. Mongol forces were ready to pounce into Syria, Palestine, Anatolia, and beyond. Every political entity in the region was ready for the onslaught that would follow. But, something miraculous happened. Möngke Khan died in August 1259. Hulagu, sensing political opportunity (it is great to be khan after all), headed to Mongolia with a large number of his forces. A small band of 10,000 warriors had been left behind to raid Syria and Palestine, which put the Mongols on a crash collision with the newly arrived Mamluk Sultanate. The two forces clashed at the Battle of Ain Jalut in September 1260. The Mamluks beat back the Mongols, and would keep them across the Euphrates until the year 1300.

However, the stage was set for a new political reality. The Mongols of the Ilkhanate were now a dominant player in the Middle East, and that threatened the Mamluks. Even more pressing was a series of communications between the Ilkhanate and Latin Christendom. In 1260, Bohemond VI of the Principality of Antioch declared allegiance to Hulagu and had supported the Mongols during their raids of Syria. Papal delegations and even French letters arrived in Mongol courts. For the Mamluks, who had fought the Crusaders and Europe for so long, this was a threat that needed to be crushed. Although the Mamluks would eventually destroy the Crusaders, the Mongol threat proved to be pervasive and ever looming.

Source: Wikipedia

Third: July, 1261 - The Byzantine Empire

Since 1204, the Byzantine Empire had been divided into a number of rump states, including the Duchy of Epirus and the Empire of Nicaea. The Fourth Crusade had radically damaged the Byzantine Empire, with Latin Crusaders creating the Latin Empire in the areas surrounding Constantinople. Obviously, the remnant states of the Byzantine Empire were not happy about this development. So, like any good rump state, the Empire of Nicaea spent several decades trying to retake former territory and killed thousands of soldiers trying to retake Constantinople.

Under Michael VIII Palaiologos, the Empire of Nicaea dealt massive blows to the Latins in 1259. The Battle of Pelagonia in the summer of that year was particularly decisive. Nicaean forces had routed the Latins and cut their polity off from key allies. In 1260, Michael VIII attempted to put Constantinople under siege, although this ultimately resulted in a stalemate. He would try again in 1261, and while Latin forces were off in a raid of a nearby island, Nicaean forces were able to clandestinely enter Constantinople, startling the poor Latin garrison that had been left behind.

Interesting to note is the hundreds of Cumans that were now in the Nicaean army. It is almost certain that the rather destructive nature of the Mongol conquests of Russia had resulted in a vast expulsion of Cumans and Kiphcaks. We know many had fled to Hungary, which would result in the Mongols invading further into Europe. We also know that many were simply sold into slavery, where they would be bought by Egyptians and turned into Mamluks. Now, we see another dimension to this as Cuman forces were decisively used in the reconquest of Constantinople.

With this victory in 1261, Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos had restored the Byzantine Empire. It was, however, a startling world to exist in. Allies were few and far. In Anatolia, the Mongols of the Ilkhanate had subjugated most of the Turkic groups living there, and as such the Byzantine Empire’s traditional enemies were weakened. Instead, Michael VIII focused his efforts westward, spending vast resources in attempts at conquering Greece. This focus however meant that aspiring leaders, like a certain Osman I (you know, of Ottoman renown) would be able to take some Byzantine territory.

Conclusions and ramblings.

What we see in these three dates is the emergence of a new political order. The Palaiologos dynasty would survive until that fateful day in 1453. The Mamluks would last until 1517. In both cases, the Ottomans would play the final role in destroying both polities. However, none of that would have been possible were it not for the Ilkhanate. The Ilkhanate, meanwhile, would only last until 1335, but their influence would be immense. Beyond the rise of the Ottomans, the Ilkhanate led to an era of uncertainty in Persia followed by a cultural height. Persian miniatures, inspired by Chinese artwork brought in by the Mongols, was emblematic of this development. Furthermore, the Ilkhanates would eventually give rise to the Timurids in 1370, who would be crucial in furthering Ottoman development. In 1402, Timur defeated Ottoman Sultan Bayezid I at the Battle of Ankara, capturing him as a prisoner and causing the Ottoman Interregnum, an instrumental period in the early Ottoman state.

One of the best examples highlighting the connections of these three dates comes in a trade agreement that emerged in 1263. The Mamluks, fearing another invasion by the Ilkhanate, needed more soldiers. To do such, they would need to increase shipments of slaves coming from the Cuman-Kipchak steppe. The Ilkhanate, meanwhile, was engaged in the Toluid Civil War and fighting the Mongols of the Cuman-Kipchak steppe, known as the Golden Horde. The Mamluks and the Golden Horde clearly saw benefits in cooperation. A strengthened Mamluk Sultanate would act as a western threat for the Ilkhanante. Furthermore, the Golden Horde recognized a number of soft benefits. Many of the Golden Horde had converted to Islam and an alliance with the Mamluks meant easy access to the pilgrimage sites of Mecca and Medina. For the Mamluks, an alliance with the Golden Horde meant a direct line of access to slaves.

The Byzantine Empire was smack dab in the middle of the Mamluks and the Golden Horde. If one tried to conduct trade by land between the two polities, you’d be talking about several months worth of travel, harsh terrain, and probable death by the Ilkhanate. Sailing across the Black Sea and Mediterranean Sea was, undoubtedly, preferable. The Byzantine Empire, meanwhile, saw an agreement with these two groups as stabilizing forces. Trade, of course, was always good, but it also meant leverage against the Ilkhanate, an important element if Michael VIII wanted to pursue his military conquests of the west. By shoring up his eastern front with the Mamluks and the Golden Horde, Michael VIII could reasonably be at ease.

And so, a trade agreement was established in 1263. The Golden Horde could freely send slaves and ambassadors through Byzantine water, which then in turn head to Egyptian ports of the Mamluk Sultanate. As these polities were young, these developments were almost certainly necessary, especially in light of the existential threat of the Ilkhanate.

Sources:

Thomas Asbridge, The Crusades: An Authoritative History of the War for the Holy Land.

René Grousset, Empires of the Steppe: A History of Central Asia.

Albert Hourani, A History of the Arab Peoples.

A bunch of scholarly articles that you will see when I finish my long form audio analysis!