History is often slanted. For much of written history, our sources represented a particular subset of a population. Education was expensive and literacy was often confined to particular socioeconomic groups. In Medieval Europe, most of our writings come from religious figures like Bede the Venerable and Ealwhine of York. In the Byzantine Empire, many literate individuals came from the imperial family and bureaucracy, such as the infamous Procopius and the well known Anna Komnene. These sources are valuable. They describe to us political history, the rise and fall of empires and kingdoms, and the movement and migration of various tribes.

However, these sources often dismiss the views of the general populace, and many of these authors outright dismiss them. We are told little about the opinions, lifestyles, and basic facts of the peasantry and urban commoners. Furthermore, writings from such individuals are incredibly rare. As we mentioned above, these people did not have the luxuries or resources to give children a literary education. For this reason, many historians are often unable to give conclusive details on what life was like for a layperson in many eras. We just don’t have the sources telling us what life was like.

We can glean some points from sources like The Canterbury Tales, which provides us at least some references to what life may have been like in Medieval England. We may get some details from plays and songs. In some cases, such as what we see in the trials of Martin Guerre in the 16th century, we’ll actually get court cases and legal records talking about some of the real struggles these individuals faced. In reality, these glimpses are simply the exception.

This is why the Cairo Genizah is such a special case for historians. Tucked away in the lower levels of the Egyptian Ben Ezra Synagogue in Cairo was a massive collection of over 400,000 Jewish documents. These preserved sources span over a thousand years, starting with the Fatimid era in the 9th century all the way up to the years of Ottoman Egypt in the 19th century. Written in Hebrew, Arabic, and other languages, these texts were incredibly well kept and legible.

The documents of the Cairo Genizah included virtually everything. There were receipts of purchases and of wages. There were records of sales, rents, and marriage agreements. A large number of these texts were diary entries and personal letters. People had corresponded to each other and talked about the most mundane things, and yet these documents may very well be the most fascinating things we’ve discovered. In many regards, the Cairo Genizah shines a light into the many lives of common Jews. Experts have identified over 35,000 individuals within the time frame of 950-1250 and many more are represented in the years following this period. For once, we are given an intimate look into the lives of the average person. We’re able to see their hopes, dreams, failures, and shower thoughts.

The Cairo Genizah offers us a window into a type of history that is often overlooked and difficult to study. As such, in this edition of the Caravanserai, I want to take a deep dive into just a handful of the stories that emerge from the Cairo Genizah and really explore what these individuals went through and what they may have been feeling.

The perils of 11th century real estate

Benjamin Franklin once wrote in a letter to Jean-Baptiste Le Roy that “in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” Benjamin Franklin was almost right. Rent, I would argue, is the final component. One of the most fascinating stories that we derive from the Cairo Genizah are the accounts of homeowners, renters, and the drama that would unfold. Perhaps surprisingly, issues of tenant rights, home prices, and the legal gray areas in between were of great contention to many of the Jews living in Cairo.

Take for instance this document dating to 1102 CE. A man named Menasse ben Yehuda was trying to sell half of a house that he had inherited from his mother for 300 Egyptian dinars to a man named Amran. The issue is that selling half of a home is rather impractical, as one could probably expect. Menasse had already sold the other half to a man named Yosef, which appears to have been done as part of a loan repayment. To make matters even more comical, it seems like Menasse was now homeless. In the end, a judge agreed that Amran would purchase Yosef’s half, thereby giving him total ownership of the home, and then Amran would allow Menasse to live at his old house and sublease it.1 From landlord to tenant with subleasing authority, this incident sounds almost like something from a modern San Franciscan court.

For whatever reason, Fatimid and Ayyubid Egypt really liked dividing homes into fractions. A document from 1139 CE describes how a house in the al-Musasa district of Fustat was split in half and then sold for 300 dinars, just as we saw in the example above.2 One home in the Tujib quarter was split into fourths, with one-fourth being sold by a father to a son for a total of 17 dinars.3 We even see discussions of women’s rights to inheritance, with one ketubba asserting that “the primary purpose of providing a woman with real estate was the creation of her of enduring economic security, which would make her financially independent.”4 This text reveals to us that many women would enter marriages with more than one property, and we once again see fractional divisions of homes, with references to a woman owning two large houses and a quarter of one to herself.

Tales of love and loss

Like our lives today, rent and mortgages were just one of many factors that complicated the lives of people. Loved ones remained an important aspect for many Egyptian Jews that lived during the Fatimid, Ayyubid, and Mamluk era. The Cairo Genizah, thankfully, did not just contain records, legal documents, and judicial decrees. We actually get diary entries and letters, granting us an ever so important window into the real, unadulterated thoughts many of these individuals had.

I think one of the most compelling stories comes from a letter by an unnamed woman. In it, she writes to a husband named al-Shaykh al-Muhadhdhab who evidently had been gone for some time. He doesn’t appear to have been missing or died; al-Shaykh simply walked away from his wife and community. Her words are stinging and somber. She tries to plead emotionally, crying that “for as long as this continues, I have become very weak. Every hour I wonder if my weakness will increase… I do not doubt in your love for me, as you must not doubt in my lasting love for you. Even if you have changed with the separation for all this time, and have been absent in my sight, my heart too has been absent.”5

Marriage remained an ever important event for many Cairo denizens in this time. We have a marriage license officiated in 1201 CE describing the union of Elazar ben Siman to a woman named Rebecca bat Joseph. This particular marriage is actually really interesting. It of course highlights to us the mindset of individuals in this time on what marriage represented and the legal facets surrounding it.

The document is riddled with religious messaging, and one of the opening lines explicitly states that “the Supreme God shall look from his elevated Heaven.” The legal text is just as evident, with witnesses from both the bride’s family and groom’s family being required. Like we see in modern wedding ceremonies, vows are given and agreed to each other. There are the normal things, like providing for each other, respecting one another, and so on. Then there’s the more specific points. For instance, the judge declared that neither the groom nor bride could “appeal to the Gentile [Muslim] courts to change the laws of the Torah.” If the groom wanted to get away from paying the 25 silver coins as the bride price, or mohar, then tough luck. Furthermore, it seems like both parties wanted to discuss rather morbid plans as they were getting married, as there’s an entire passage on inheritance here.

“And if, God forbid, this bride leaves this world without a living child from her husband, all that will belong to her will return to her heir from her father’s family, and her husband will not owe anything from her delayed mohar.”6

However, one of the most fascinating descriptions from this document is the geographic origins of Rebecca and her family. It is revealed that Rebecca had come from the lands of the Byzantine Empire, some leaving the city just before the Fourth Crusade’s disastrous sacking of the city. Although no further information is provided about why Rebecca’s family may have left the Byzantine Empire, it is a helpful reminder of Egypt’s status as an international hub. We know that caravans from the Silk Roads, pilgrims from the Maghreb, and Italian merchants from Venice and Genoa all made their way down to Egypt, and here we have a Jewish family from either Greece or Anatolia migrating to Cairo.

A world on the cusp of the Crusades

This international dimension is a helpful reminder. Egypt, for a long portion of its history, has been a land of connections. From east to west, people have moved through the land, bringing their goods, cultures, and news with them. My favorite document from my brief examination of the Cairo Genizah comes from a letter written by a man named Yeshua ben Ismail.

Dated to 1062 CE, we actually arrive in a rather fascinating era of Islamic history. Just decades prior to the First Crusade, the account provided by Yeshua hints at rumblings of changes to come. We know that in this time, the Umayyad Caliphate of al-Andalus had actually collapsed and entered into the First Taifa period, with the various Spanish monarchies taking bits of territory from the split Muslim polities. A similar case had emerged in Sicily. Muslims had occupied the island since 831 CE, but by 1044 CE, this region had also splintered into several warring factions. In Yeshua’s letter, he recounts to us an incident he had at the docks of Fustat.

“The boat of Mujahids arrived from Mazara (Sicily) after a passage of seventeen days. A number of our Spanish coreligionists traveled in it, among them Abu Jacob-Joseph, whose son-in-law is in Misr (Cairo-Fustat)... I went to them and asked them about news from Sicily. They reported good and reassuring news, namely, that Ibn al-Thumna had been killed and that the situation in the place had become settled.”7

Now, this passage is actually extremely illuminating. First, let’s talk about the “Spanish coreligionists.” It is very important to understand that while al-Andalus had a reputation of being a religiously tolerant place, where Jewish individuals like Yusuf ibn Nagrela could rise to the position of vizier, this was never really stable or ever present. In the wake of the First Taifa period, many individuals in al-Andalus were alarmed by the fall of the Caliphate and subsequent losses to the Christians in the north. Accusations were thrown to all individuals, and Andalusian Jewish communities were often at the forefront. Attacks, massacres, and pogroms did become more common throughout the 11th century, and anti-Semetism increased during the subsequent Almoravid and Almohad eras. The Jewish vizier Yusuf ibn Nagrela, for instance, was crucified in 1066, and many of the Jews living in Granada were massacred. The Jews met by Yeshua had only escaped such an incident by four years. It seems like Fatimid Egypt became a place for many Andalusian Jews seeking to flee the turmoil in the area.

When talking about the “Mujahid” Yeshua met, we actually have a very good idea about where they were fighting. In Sicily, the lands were split between four different taifas, and the Taifa of Syracuse, on the southeast end of Sicily, was ruled by a man named Ibn Thumna. Ibn Thumna had made a reputation for himself as someone willing to use Christian mercenaries, particularly Norman ones, in fights against the other taifas. Muslim mercenaries were encouraged to sail to Sicily to fight Ibn Thumna and his heretical force.

Ibn Thumna indeed did die in 1062 CE, and one can reasonably assume that these warriors were in fact mercenaries who did battle against Ibn Thumna. The issue is that Ibn Thumna’s recruitment of Norman mercenaries set a chain of reactions that slowly gave the Normans more and more control over Sicily. One of the leaders hired by Ibn Thumna was none other than Roger de Hautville, the brother of Robert Guiscard.8 Robert, as we may know, was a Norman adventurer that had carved territory for himself in the Italian lands of Apulia and Calabria. With these acquisitions, Robert then attempted to conquer Byzantine territory in the 1070s and 1080s, while his son Bohemond I would be one of the most infamous leaders of the First Crusade, claiming the Principality of Antioch for himself.

Robert’s brother, Roger, was looking for similar glory. After the Battle of Misilmeri in 1068, Muslim attempts at controlling Sicily were destroyed. Over the next few decades, Roger would be able to consolidate control over the entirety of Sicily, establishing himself as a count and bending the knee to his brother. Despite the efforts of Yeshua’s “Mujahid” warriors, the Normans would eventually control southern Italy and Sicily, establishing for themselves a new polity that, for a time, embraced a cultural melting pot known as the Arab-Norman-Byzantine synthesis. Indeed, the Muslim mercenaries that had fought Roger would eventually join him. In 1098, Roger was fielding armies that comprised mostly of Muslims, and his descendent Roger II would have an elite corps of bodyguards that was entirely Muslim.9

This letter by Yeshua then is very interesting, as it previews a world in the midst of very large political and demographic change. As Christian forces mounted pressure over their Muslim counterparts, a number of causal relations emerged. Jews were forced to flee al-Andalus. Arab and Berber mercenaries headed to Spain and Sicily. Fatimid Egypt increasingly became a land for refugees and migrants. In just three decades, the tides of change will crash over with Pope Urban II’s speech at the Council of Clermont in 1095. However, the resulting First Crusade was only ever the first in a series of events that were being witnessed by Yeshua ben Ismail.

Conclusion

Throughout our exploration of the Cairo Genizah, we’ve seen an incredible array of different stories. We are able to get a glimpse into the mundane economic elements of Egyptian Jewish life in the Medieval era. We have direct figures on home values, actual examples of rent, and the legal questions that emerged from real estate ownership. We have seen how marriage contracts were arranged, what inheritance amounted to, and even aspects of gender expectations. There are stories of love and loss, tales of glory and triumph.

The best part is that these stories are just a few random samplings. The Cairo Genizah spans hundreds of thousands of documents, crossing several centuries of history. Unlike many other textual sources, we are given an important window. These were not the lives of kings, emperors, and khans. Instead, we are able to understand the thoughts, hopes, and dreams of the average person. Sure, there may have been scribes writing on behalf of these individuals, but the significance of this trove cannot be overstated. For far too long, history has been defined by those with the means to write it down. Literacy was a privilege few could literally afford. The Cairo Genizah reminds us that the vast majority of individuals, those Yeshuas and Rebeccas of Egypt, were just as worthy to be discussed by history.

Legal document of Menasse ben Yehuda, January 22, 1102, AIU VII.D.7, Ed. Goitein and Friedman, Princeton Geniza Project, Princeton, New Jersey.

Deed of sale of one half of a house, September 1, 1139, Bodl. MS Heb. d 66/99, Princeton Geniza Project, Princeton, New Jersey.

Deed of sale in which a father sells to his son, 1233, CUL Add.2586, Princeton Geniza Project, Princeton, New Jersey.

Kettuba in the hand of Halfon b. Menashe, ENA NS 2.45, Princeton Geniza Project, Princeton, New Jersey.

Letter from a woman to her distant husband, Bodl. MS Heb. a 3/12, Princeton Geniza Project, Princeton, New Jersey.

Kettuba for Rebecca bat Joseph of Byzantium and Elazar b. Simon, October 13, 1201, CUL: T-S 16.67, Friedberg Genizah Project, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

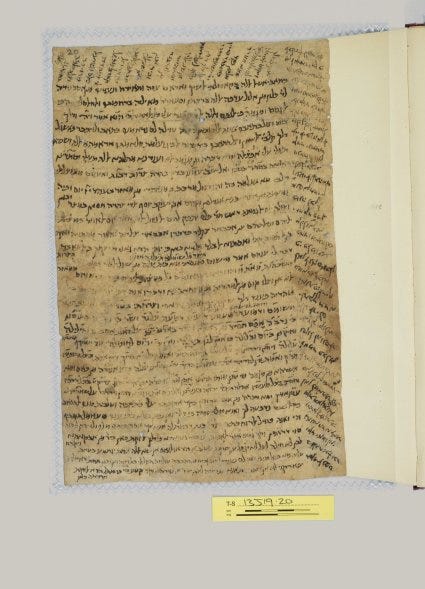

Letter from Yedua’ b. Isma’il al-Makmuri in Alexandria, August 1062, CUL: T-S 13J19.20, Friedberg Genizah Project, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Ian Almond, Two Faiths, One Banner: When Muslims Marched with Christians across Europe's Battlegrounds Paperback (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2011), p. 52.

Ibid.

This is the first post I read - and loved! In particular, I enjoyed reading the transcription of the marriage document which reminded me of present marriage contracts in Iran (https://www.academia.edu/41581639/_By_the_elders_leave_I_do_Rituals_ostensivity_and_perceptions_of_the_moral_order_in_Iranian_Tehrani_marriage_ceremonies_Sofia_A_Koutlaki_Independent_researcher), and also common law practices from my native island Kassos in the south Dodecanese, Greece. The dissemination of the concept of cultural continuum is promising in our fragmented world: my newsletter looks at intercultural communication, another way of the approximation of people. I look forward to reading more of your posts. https://somelittlelanguage.substack.com/

Great article, Edwin! It's easier to feel a connection with (and put yourself in the world with) ordinary folks of any time than with the kings and queens, and it's more interesting, in many ways. Will and Ariel Durant's "Story of Civilization" series purported to strive to show the lives of the non-rich non-famous non-royal, and I think they did pretty well with it--one of the things I loved about those books. Those books are dated now, and much more general than your focus, but the first few volumes might interest you.